I don’t think any of us can practice total open-mindedness because we continually have to make decisions and in order to make decisions we usually have to come to some sort of conclusion even if that means not making a decision at all.

I don’t think any of us can practice total open-mindedness because we continually have to make decisions and in order to make decisions we usually have to come to some sort of conclusion even if that means not making a decision at all.

Practicing open-mindedness, isn’t universal a characteristic we are born with. To be effective leaders and managers we often have to develop the crucial habits of self-reflection, observation, challenging beliefs and perceptions. For many of us, until something in life looms up to challenge us, then we simply don’t make the effort, or we just don’t realise, we should be questioning our daily paradigm.

Some of the pitfalls of not practicing open-mindedness are:

- Having a Groundhog day experience

- Seeing other people grow away from you

- Staying in a miserable situation/state/relationship

- Giving up on dreams

- Feeling like a victim

- Limiting other people

- Stereo-typing situations or people

- Coming to faulty conclusions

Within my coaching practice, I regularly see clients or people they work with, struggle to overcome fixed beliefs, values, judgments or even wishful thinking that get in the way of changing, or moving forward, in a situation.

The most common reasons they struggle is that it sometimes feels painful to have to a) acknowledge there is another way to look at things, and they might have gotten it wrong, b) they have a need to be right, or c) they have to track back to painful situations in their past which formed their limiting beliefs.

Byron Katie has a brilliant method which demonstrates how we can turn around beliefs and ways of thinking to find relief from uncomfortable or painful emotions. You can find out more about Byron Katie’s work in her series of books which started with.

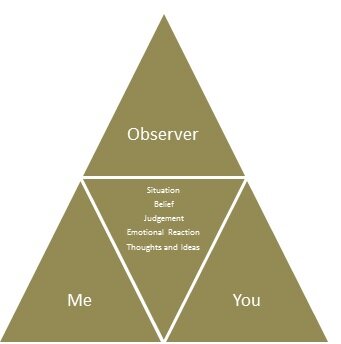

For me, there is a simple formula which can help the process of practicing open-mindedness, and I call this “The golden triangle”. In essence, this involves looking at tricky situations in 3 ways. From your own perspective, the perspective of the other(s), and then as an observer

The role of the observer is essential in this process because it is in the observer’s role when it is possible to remain neutral, detached and to see the bigger picture.

The possibilities are endless. When you come to make decisions, using the perspective of an observer you come to realise:

- For every argument “for”, there is a counterargument

- Beliefs, thoughts, perceptions and ideas are fluid and flexible

- Values can change depending on different situations

- Stories and myths are helpful to unraveling paradigms or thought patterns

We all need to form paradigms, beliefs and ways of thinking and making decisions which work for us, we couldn’t get through our daily lives without such a structure. But if that structure isn’t working for you, then it’s time to visit the Golden Triangle and practice your muscle of open-mindedness.

As always Christine – valuable and succinct advice, thank you.

Thanks for the positive feedback Mark. appreciated. Hope all is well with you, and hope you have a lovely weekend :) – Christina

In collegiate debate, the observer was the judge. The process was rhetoric with an object of win/lose. To lose often prompted two reactions:

1.) the judge was biased;

2.) a feeling of inadequacy (with all of the logical downward spirals that normally follow the lowering of attitude).

I like what Byron is proposing, as it establishes a forum for dialogue instead of just argumentative rhetoric. And the observer, when looking for resolution, can help make communication work. Thanks, Christina, for sharing.

Thanks Van, it’s a good point, the observer must always be win/win and objective :) Always enjoy your wise responses – have a great weekend